Personalized movie recommendations based on script text

Let's say I'm a computer and I don't know anything about movies. But I can read movie scripts. My human friend wants to know which movie to watch. How can I help her?

Step 1: Predicting movie genres from scripts

Maybe my friend wants to watch an action movie?

If I have the script for a movie, how can I tell if it's an action movie or not?

First, I collected 825 scripts from IMSDb. Then for these same 825 movies, I checked to see if they were tagged as 'action' movies on MovieLens. I end up with 106 action movies, including:

- Terminator

- Ninja Assassin

- Crank

- X-Men Origins: Wolverine

There also 721 non-action movies, including:

- Mary Poppins

- Gandhi

- Duck Soup

Using these 825 movies and their scripts, we want to build a model that correctly predicts whether or not a movie is an action movie, based on its script. For these 825 movies, we already know the answer, but the exciting part is that then we can apply the same model to new movies that we don't know anything about to figure out if they should be called action movies.

Before we get into the details, it should be noted that this isn't a very practical thing to do. Classifying movies by genre is already something that is done (by humans) for all movies, and it's not something that computers are likely to do better than humans. This is not a task that really makes sense for a computer. However, while it may not be that useful, it's a fun exercise, and it's a warm-up for Part 2, which is something more appropriate for computers.

So how do we do this?

Bag of words

The bag-of-words model is a trick that helps computers interpret written text. We will use this model for our analysis of movie scripts. Bag-of-words means that we only care about the frequency of words in the text. We do not care about the order of words at all. In other words, these three sentences are all equivalent according to the bag-of-words models:

- Houston, we have a problem.

- We have a problem, Houston.

- A we Houston problem have.

Although we lose a lot of information about the movie by doing this, it makes it easier for the computer to analyze.

Random forest

We will use the word frequencies from the bag-of-words model as features in a random forest classifier.

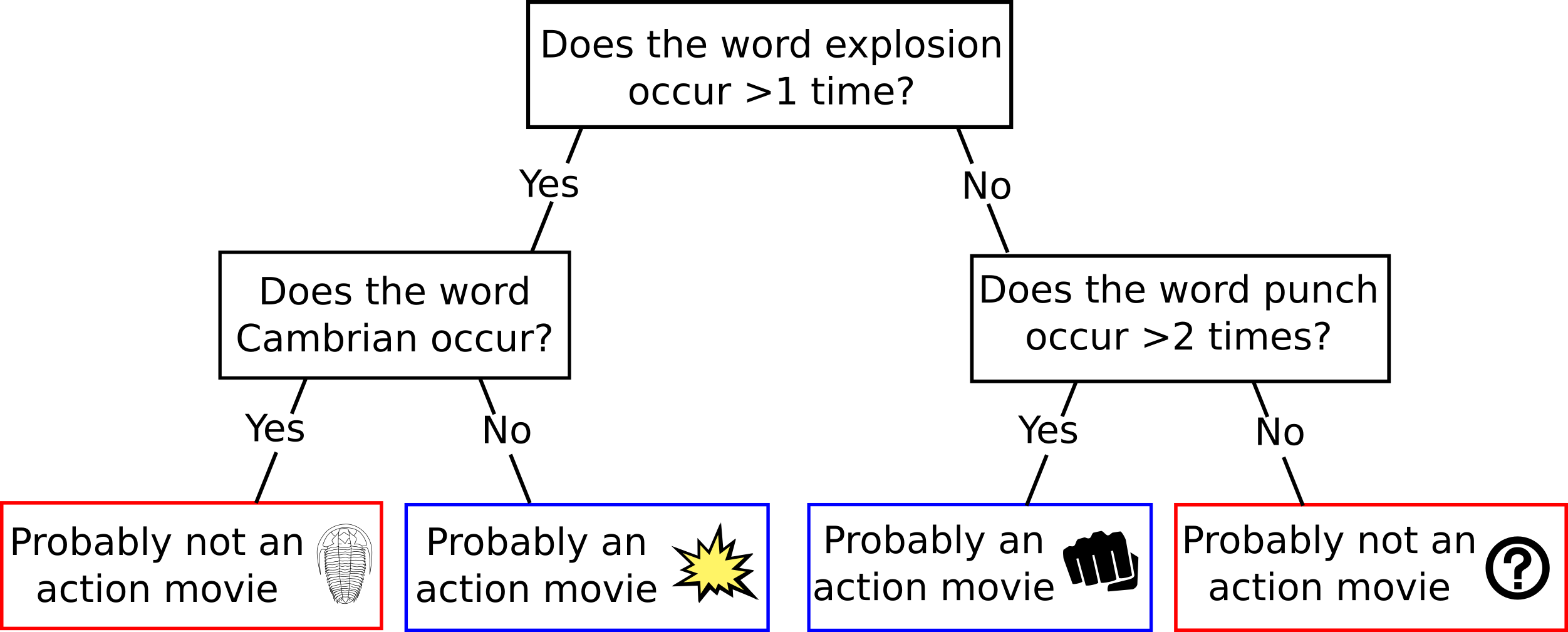

Random forests are a variant of the basic decision tree method. The following is a simplified example of what a single decision tree would look like using bag-of-words:

A random forest consists of a collection of many such decision trees (here we use up to a thousand decision trees in a single model). Each tree is random in that the words used both the words used to distinguish and the movies used to train the tree are randomly selected.

The computer learns the correct decision trees by examining the training dataset (the 825 movie scripts for which we have both scripts and action tags available).

Results

The computer reads in all 825 movie scripts, then performs lemmatization on each word, which mean that each word is transformed to a word you would find at the beginning of dictionary entry (for example, "explodes" is transformed into "explode" and "explosions" is transformed into "explosion"). Stage directions and character names are not removed from the script.

After lemmatization, we find the 10,000 most common words found across all the movie scripts. These words will be used as predictors.

At this point, every movie has been tagged by a human as either action or non-action. We also have 10,000 predictors, which are just counts of how many times each word has appeared in the script. We train a random forest model to predict the action tag based on the word counts.

We can use cross-validation to estimate how accurate the model will be on data that it hasn't seen yet. Cross-validation ensures that we don't cheat by using information about the movie we are predicting to make a prediction about itself.

The cross-validated accuracy is 92%. This means that if we get a new movie where we're not sure if it's an action movie, we will label it correctly 92% of the time. 92% sounds pretty high. But wait! Only 13% of our movies were action movies to begin with. That means that if we predicted that every movie was non-action, we would already have 87% accuracy. Let's look at the cross-validated results in more detail:

- Accuracy rate for movies that are truly non-action: 99% (712/721)

- Accuracy rate for movies that are truly action: 46% (49/106)

Let's look at our predictions for the movies listed above:

Action movies:

- Terminator: action

- Ninja Assassin: not-action

- Crank: not-action

- X-Men Origins: Wolverine: action

Non-action:

- Mary Poppins: not-action

- Gandhi: not-action

- Duck Soup: not-action

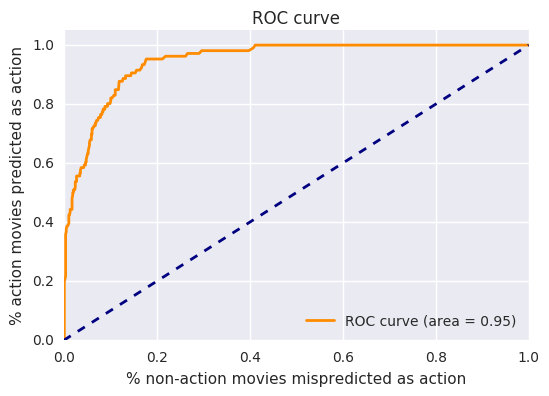

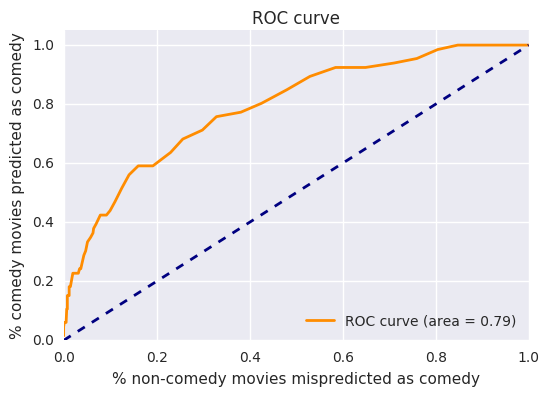

Is there a way to correctly classify more action movies? Yes, but only if we are willing to misclassify more non-action movies. This trade-off is shown on a ROC curve:

This shows that we can correctly predict about 80% of action movies, if we are willing to misclassify about 10% of non-action movies.

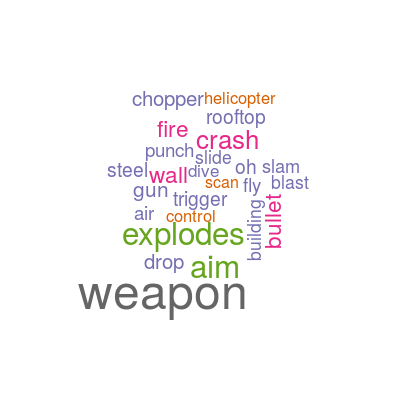

Action words

What words are most important for determining if a movie is an action movie or not?

What about comedy?

The bag-of-words model is not perfect at predicting action movies, but it does recognize salient features (words having to do with violence and fast motion) that help identify action movies. It turns out that it is not equally good at predicting comedies, which make up 8% of our dataset.

If we want to correctly predict 80% of comedies, we will end up mispredicting about 40% of non-comedies. Why is this so bad? Computers just aren't good at jokes.

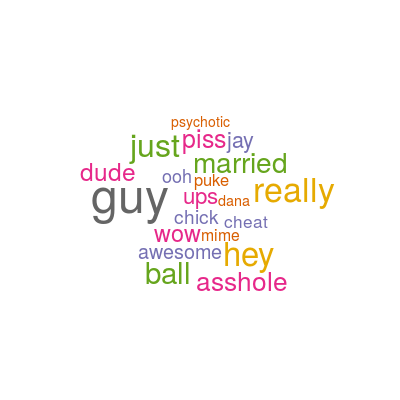

These are the words most predictive of comedy:

Not very funny, huh? Maybe the jokes are hidden in the order of the words, which bag-of-words explicitly ignores, rather than in the words themselves. Also, perhaps the genre of comedy is broader than action. The words that identify a romantic comedy might be different than the words that identify a dark comedy.

So it turns out that bag-of-words is better at identifying certain aspects of movies than others.

Part 2: Predicting ratings for many users based on scripts

If we're in the business of recommending movies, why not go all out and make personalized predictions for the whole world, predicting how much each person will like every movie ever made. One technique for doing this is collaborative filtering.

Collaborative filtering

Collaborative filtering refers to methods that use users with similar tastes to make predictions. If people who like Inception tend to also rate the Matrix highly, and Leo likes Inception, it's reasonable to predict that Leo will also rate the Matrix highly.

MovieLens provides a dataset of 20 million movie ratings of 27,000 movies by 138,000 users, so this is a great dataset for testing a collaborative-filtering algorithm.

So what does this have to do with scripts? Collaborative filtering has the weakness that it depends on existing ratings. If a new movie comes out that that few people have seen yet, collaborative filtering will not be able to make good predictions. This is known as the cold-start problem. We want to see if having access to the script will help with this problem. Can the words in the script help predict how much a given user will like it?

The factors

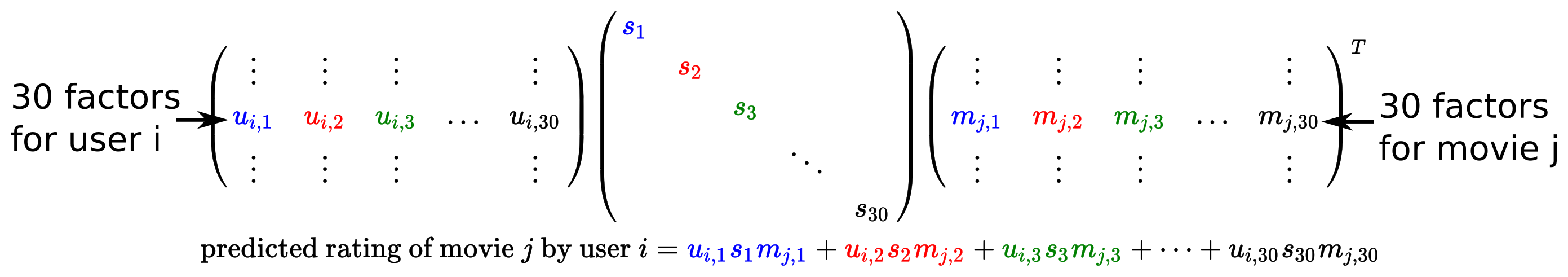

One algorithm for doing collaborative-filtering tries to discovers a certain number (let's say thirty) of hidden factors that characterize people's taste in movies. Both users and movies are assigned thirty factor ratings, one for each factor, which are inferred by the ratings of movies they have already seen. A specific users is predicted to like a specific movie if the factors align between the user and the movie. So if Anchorman has high "factor 1" and low "factor 2", and Jim also has high "factor 1" and low "factor 2", then we predict that Jim will rate Anchorman highly. While if Jules has low factor 1 and high factor 2, we predict that he will not like Anchorman. This is encoded in three matrices as follows:

The algorithm that discovers all these factor values (filling the matrices above), is provided by the softImpute package for R.

To make this a little more concrete, let's look at the factors found in the MovieLens rating dataset.

The factors are ordered by importance, so we start by looking at Factor 1. These movies have the highest Factor 1 value:

- Taxi Driver

- Fargo

- Trainspotting

- Being John Malkovich

- Ed Wood

- Apocalypse Now

- Reservoir Dogs

- Chinatown

- Rushmore

- Brazil

And these are the movies with the most negative Factor 1 value:

- Pearl Harbor

- Independence Day

- Entrapment

- Wild Wild West

- Air Force One

- Judge Dredd

- Cliffhanger

- Swordfish

- Runaway Bride

- Rock, The

These factor values are determined by the computer solely by looking at users' ratings of movies and not knowing anything about the content of the movie. However, it looks like the computer has "discovered" some property of movies that corresponds to what we might call unorthdox (high factor 1) vs. straightforward (low factor 1).

Just for fun, let's look at factor 2 also. These are the most factor 2 movies:

- Sleepless in Seattle

- Shakespeare in Love

- Little Mermaid, The

- Mary Poppins

- Pretty Woman

- Big

- Finding Nemo

- Toy Story

- It's a Wonderful Life

- American President, The

And the least:

- Natural Born Killers

- Fight Club

- From Dusk Till Dawn

- Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

- Event Horizon

- Trainspotting

- Big Lebowski, The

- Pulp Fiction

- American Psycho

- Reservoir Dogs

The computer is picking up on something that seems to correspond to the distinction between upbeat movies (high factor 2) and disturbing movies (low factor 2).

Predicting factors from scripts

So far we haven't used any data from the scripts. The factors may be interesting on their own, but we would like to be able to predict them using the words in the script. To do that, we use a similar procedure to what we did for predicting genres, using the same bag-of-words model. There is a technical difference that means we have to do random forest regression rather than random forest classification. This is because what we are trying to predict is a continuous variable (the value of a factor can be any number, including negative numbers and decimals) rather than a binary choice (action or not-action).

It turns out that, just like with genres, some factors are easier to predict than other. Factor 4 is an interesting case. Here we show the six movies with the most extreme Factor 4 values, and the words that best predict Factor 4:

We can look at the accuracy of our factor predictions, but what we were are really interested in is predictions of user ratings, which are based on our predictions of factors.

How does it do

So we can predict factors based on movie scripts. But what we really want to do is to predict how each user will rate a given movie. We can do this by combining our predicted movie factors together with the users' known factors.

To see how well we can infer users' ratings, we use the scripts to make cross-validated predictions of each of the thirty factors for all of the 825 movies we have scripts for. We then uses these factors to predict ratings for all 138,000 users in the MovieLens database for all of these 825 movies. Some of these users will already have rated some of these movies. We can test how good our predictions are by comparing the predictions with the actual ratings. The accuracy of our measurements can be summarized by the root mean square error (RMSE).

There is one more complication we need to address before we can make all these predictions. To calculate predictions, we need, in addition to the factors, the average rating of each movie (I skipped over this fact above). We try to predict the average ranking using the same method we used to predict the factors, that is, building a random forest model based on the words on the script. Not surprisingly, the computer does not do great at figuring out what is a good movie or bad. There is another approach we can take, which is to combine our predicted factors with the true average rating of the movie to make our predicted ranking. This is slightly cheating, because it does not solve the true cold-start problem. If a movie is brand-new, there will be no ratings of it and no way to know what the average rating would be. However, this is still a useful approach for dealing with what we might call the "cool-start" problem: if a movie is new enough that it only has reviews from 50-100 users, we do not have enough information to accurately infer all 30 factors from user ratings, but we do have enough information to estimate the average rating. If this is the case, and we have access to the script, then our semi-cheating approach could work well.

So how do the predictions actually do? The first method, which predicts the average rating from the script, has an cross-validated RMSE of 0.907. The second method, which uses the true average rating, but predicts the factors from the script, has an RMSE of 0.804.

But what do these numbers mean? How good are these predictions? To help us interpret these numbers, we can compare them with the results of certain simpler prediction systems, to see if all the extra work we have done has actually paid off.

One simple prediction would just be to predict that each user will rate a movie according to that user's average rating. So if the average of all the ratings Vito has made is 3.5, we predict he will rate all new movies as 3.5, while if Michael's average rating is 3.9, we predict all his ratings as 3.9. This simple prediction system has an RMSE of 0.914. This should be compared to our first method, with an RMSE of 0.907. In this case, all the extra information we have from the movie scripts has only made a tiny difference. This is because the computer is bad at determining the overall quality (average rating) of a movie.

A slightly better method might be to use both the average rating of a user and the average rating of a movie to make each prediction. This gives us an RMSE of 0.845. Since this method also uses the true average rating of a movie, it should be compared to our second method, which has an RMSE of 0.804. With this method, where we don't need to predict the average rating, the improvement is more significant.

Finally, we can compare to the gold-standard of predictions, which is our original prediction system, using the factors infered by user ratings, rather than the factors derived from scripts. This method has an RMSE of 0.661. We can conlcude that adding in the script information gets us 20% of the way from the naive method (which knows nothing about the movie except the average rating) to the best predictions.

The code for this project is available here.